By New Chigen

MASSACHUSETTS (CONVERSEER) – MIT neuroscientist Ev Fedorenko has identified a language network similar to a “biological version of ChatGPT” by scanning the brains of approximately 1,400 people. This network is not responsible for thinking or emotions; it focuses solely on mapping words to meanings and assembling them into sentences. This research reveals the separation between language and thought, prompting us to re-examine the hidden mysteries of the brain.

If I told you that a “biological version of ChatGPT” is running in your brain, would you believe it?

This is not an analogy; our brains do indeed have a neural system specifically designed to process language.

It is not responsible for thinking or emotions; it is only responsible for one thing—matching words with their meanings and then piecing them together into sentences.

This system is called the “language network” by neuroscientist Ev Fedorenko.

The brain’s innate LLM system

Many people may feel that language and thinking are the same process, and that the process of finding words is itself a form of thinking.

But are human language and thought the same thing?

Is language the core of thought, or a completely independent process?

In response, Fedorenko offered a somewhat counterintuitive perspective:

Language is not the same as thinking; it is more like the “interface” and “outer packaging” of thinking.

For many, finding the right words is an integral part of thinking itself, rather than the product of a separate system.

She calls this specialised system, which is independent of thought, a “language network,” used to map the correspondence between words and their meanings.

Fedorenko envisioned it as an enhanced parser:

“It’s like a map, telling you which part of your brain stores which type of meaning, and like an enhanced parser, helping us piece together the language.”

The real thinking and interesting things all happen outside of this language network.

In fact, long before ChatGPT came into being, Fedorenko had been collecting evidence of the language network in the human brain for the past 15 years and found that it had many similarities with the Large Model (LLM).

In a sense, we do indeed carry a “biological version of ChatGPT”: a language processor without a mind.

Fedorenko’s research may offer some comfort: a machine may be able to generate fluent text, but it still cannot think.

In his lab at MIT, Fedorenko has spent 15 years accumulating biological evidence about language networks.

Unlike large models, human language networks do not randomly string words together to form sentences that sound plausible.

It is more like a translator that connects external inputs (what you hear, see, or even sign language) with the meaning representations in other areas of the brain (such as episodic memory and social cognition, which LLM does not have).

Moreover, the human language network is not very large; if all related organisations were gathered together, it would only be the size of a strawberry.

Although it is small, the impact of damage to it can be enormous.

For example, a damaged language network can lead to various forms of aphasia. In such cases, a person’s complex thinking still exists, but they are trapped in a brain that cannot express itself; sometimes, they can’t even distinguish the words spoken by others.

By scanning the brains of 1,400 people, she discovered the “language network” in the human brain.

Fedorenko grew up in the Soviet Union in the 1980s and developed an interest in languages from a young age.

At her mother’s request, she learned six languages: Russian, English, French, German, Spanish, and Polish.

With her outstanding academic performance, she eventually received a full scholarship to Harvard University.

She majored in linguistics at Harvard University, but during her studies, she discovered the limitations of linguistics.

“These linguistics classes are interesting, but they’re more like solving puzzles than explaining how the real world actually works.”

So she studied psychology.

In 2002, she graduated from Harvard University with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and linguistics.

Fedorenko then pursued graduate studies in cognitive science and neuroscience at MIT, where she received her PhD in 2007.

During this period, she began working with Nancy Kanwisher, who first discovered the fusiform face region, an area specifically responsible for recognising faces.

Fedorenko wanted to find the corresponding area in the brain for language, but at the time, the research foundation in this area was quite weak.

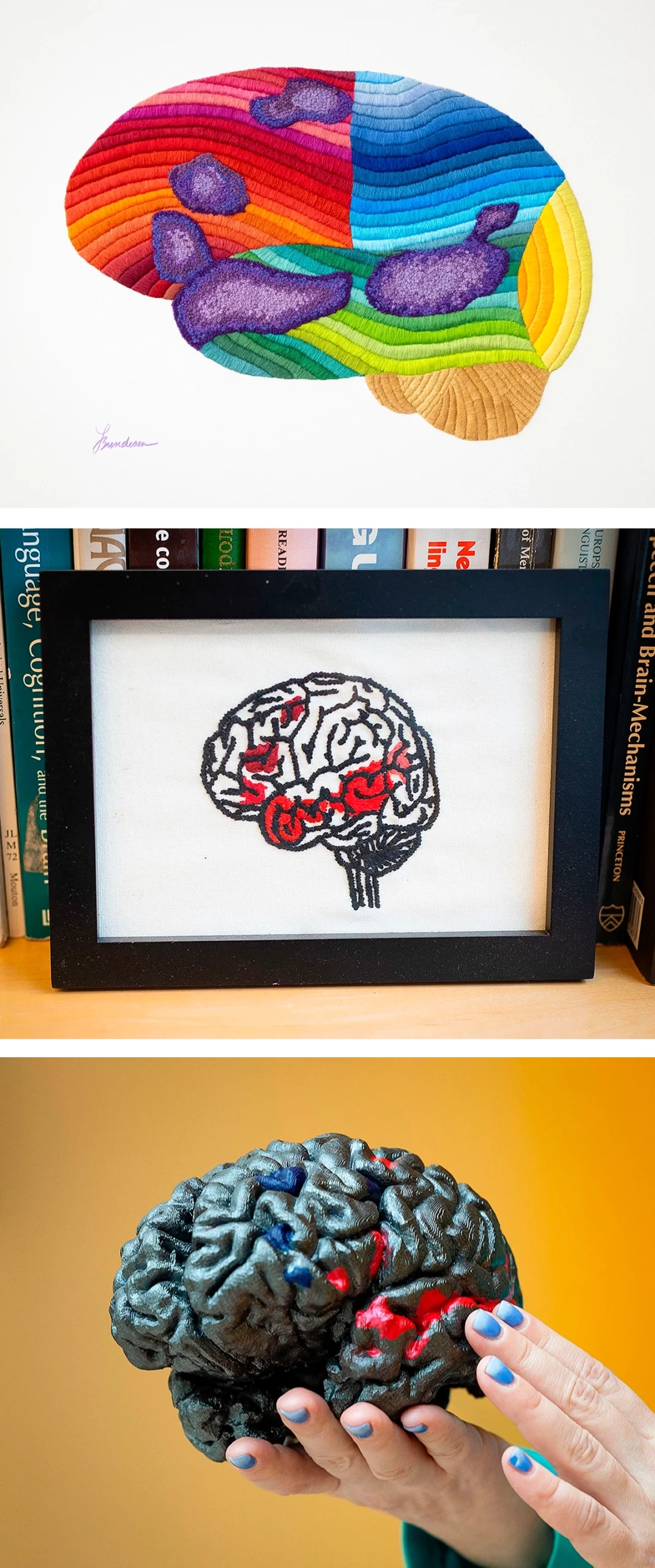

In brain scans of approximately 1,400 subjects, Fedorenko identified a pervasive language network, which she defined as “an organisation that is always responsible for language computation.”

Following a series of accumulated research findings, Fedorenko published a review article in Nature Reviews Neuroscience in 2024.

She defines the human language network as a “natural category”—a natural, independently formed functional unit that specialises in language processing, existing “in the brain of every typical adult.”

What is a language network?

In the adult brain, there is a core set of interconnected systems responsible for calculating language structure.

They store the mapping between words and their meanings, as well as the rules for combining words into sentences.

These are the things we learn when we learn a language.

Once we master them, we can use this “code” very flexibly: as long as you know a language, you can turn an idea into word order.

Fedorenko stated that the language network, like other organs of the human body, is a natural category with a physical structure that indicates a specific location.

For example, the fusiform gyrus is a clearly defined functional unit.

In the language network, most people have three regions in their frontal cortex, all located on the lateral side of the left frontal lobe.

In addition, there are several areas distributed along the sides of the middle temporal gyrus, which is a large, thick tissue extending along the entire temporal lobe.

These constitute the core of the language network.

We can see their overall nature from multiple perspectives.

For example, when people are placed in an fMRI scanner to observe differences in language processing compared to control conditions, these areas always change together.

Fedorenko says that they have scanned about 1,400 people so far and have been able to create a probability map showing the most likely locations for these areas.

Although there are slight differences between individuals, the overall pattern is very consistent.

Within these large areas of the frontal and temporal lobes, each person has some organisation that reliably performs language computation.

The language network differs from other known language-related brain anatomical regions, such as Broca’s area.

Fedorenko believes that Broca’s area is more of a planning area for vocalisation.

It mainly calculates the actions required to pronounce these sounds based on the sound representation of speech, directs the activity of the mouth muscles, belongs to the downstream of the language network, and receives structured language information transmitted from the language network.

The language network is neither responsible for vocalisation nor for thinking; it is essentially a low-level perception and motor system, serving as an interface between itself and a high-level system of abstract meaning and reasoning.

Fedorenko mentioned that humans mainly use language to do two things.

The first is expression: a vague idea pops into your head, and then you pick out a set of words from your vocabulary (not just words, but also larger structures and combinations) to express this idea.

Then the language network gives the word order to the motor system, allowing you to speak it, write it down, or sign it.

The second is understanding: after sound enters the ear or light enters the eye, the perception system first processes the input into word order.

Then the language network parses it, finds familiar chunks in the word order, and points them to meaning representations stored elsewhere.

For both expression and understanding, this system is a constantly updated “form-to-meaning mapping repository”.

Once we master this code, we can not only express our thoughts, but also understand what others are saying.

The function of language networks is communication. So, how specialised are language networks? Are there cells that specifically respond to certain discourses?

Fedorenko argues that language depends on context, and therefore speculates that the encoding within a language network system may be somewhat distributed, with neurons that may be particularly responsive to certain aspects of language.

For example, some cells in language network areas may also have similar responses to written and auditory language.

When discussing patterns or characteristics of language networks, Fedorenko argues that the brain’s general object recognition mechanisms are very similar in level of abstraction to language networks.

This is similar to how the inferior temporal cortex stores fragments of object shapes, and the fusiform gyrus stores “a template of a face”.

We use these representations to identify objects in the real world, but they themselves are not directly related to our knowledge of the world.

Take the meaningless sentence “Colourless green thoughts sleep angrily” as an example. We can roughly understand its structure, but we cannot apply it to any real-world knowledge.

Research by Fedorenko and other teams confirms that language networks respond to these meaningless sentences with almost the same intensity as they respond to meaningful sentences.

This does not mean that the language network is “stupid,” but rather that it is indeed a relatively shallow system.

Fedorenko agrees with the statement that “everyone has an LLM in their head.”

She believes that language networks are similar to early large models in many ways: learning the rules of language and the relationships between words.

In reality, you might encounter someone who speaks very fluently, but after listening for a while, you realise they haven’t said anything substantial, and their brains haven’t suffered any damage.

This indicates that they only activated the language network in their brains, while the thinking part was completely unused.

Although it may sound counterintuitive that human language originates from an “unconscious” system like ChatGPT.

Moreover, Fedorenko initially believed that language was central to higher-level thinking, but her later research did not support this hypothesis.

As early as 2011, she was already well aware that all parts of the language network were highly specialised for language.

“For scientists, the only option is to update their knowledge and continue exploring.”