By Efiom Attoe

CALABAR (CONVERSEER) – The recent submission of the Federal Government’s Inter-Agency Committee report to the Revenue Mobilisation, Allocation and Fiscal Commission (RMAFC) may appear, on the surface, to signal a victory for Cross River State. After years in the wilderness, Cross River is projected to be relisted as an oil-producing state with over 100 verified oil wells. However, a closer look at the implications of the 2012 Supreme Court judgment reveals a more sobering reality: Cross River has still effectively lost out to Akwa Ibom State.

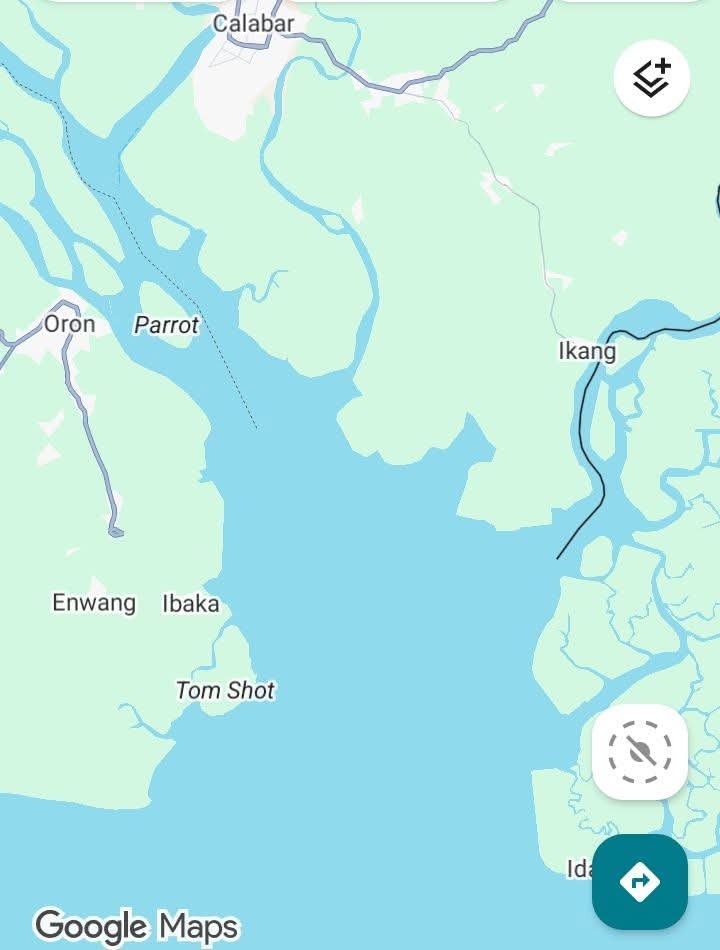

At the heart of the matter is the lingering consequence of the Supreme Court decision, which redefined offshore boundaries following the ceding of the Bakassi Peninsula. That judgment stripped Cross River of 76 oil wells, transferring them to Akwa Ibom. More than a decade later, those 76 wells remain firmly retained by Akwa Ibom, pending further judicial interpretation.

Despite having the highest number of newly discovered surface coordinates—over 245—during the 2017–2025 verification exercise, Cross River could not overcome the legal shadow of that ruling. Instead, Akwa Ibom is expected to benefit from the highest number of the newly attributed oil wells, i.e., over 100 wells arising directly from coordinates situated within Cross River State.

In effect, Cross River not only failed to recover the 76 oil wells lost in 2012 but is also projected to lose over 100 newly discovered wells to Akwa Ibom as a consequence of the same Supreme Court interpretation. While Cross River may regain oil-producing status with more than 100 wells—largely from OML 114 within its onshore maritime territory—the gains pale in comparison to what has been ceded.

This means that although Cross River will likely celebrate its return to the oil-producing states’ list, the structural imbalance created by the court ruling remains intact. Akwa Ibom continues to consolidate its advantage, both by retaining the 76 previously disputed wells and by acquiring over 100 additional wells from the Cross River State’s newly discovered 245, tied to boundary interpretations.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court judgment continues to shape the allocation landscape, and for now, Akwa Ibom remains the principal beneficiary of its long-term implications.

As the report awaits presidential approval and implementation, the fundamental question persists: can Cross River truly claim victory when it has only regained status but not parity?