By Emmanuel Nicholas

UYO (CONVERSEER) – By way of public announcement, Senator Godswill Akpabio, President of the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and Chairman of the National Assembly, has indicated that the process to amend the Electoral act amendment Bill will be completed by the end of January 2026, with the declared objective of enshrining a definitive electoral calendar and thereby reducing uncertainty in the conduct of national elections.

Historically, both the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and the National Assembly have pursued statutory reform of electoral law in the run‑up to and in the aftermath of general elections; such reform initiatives are in the nature of iterative statutory refinement to address recurring defects and evolving governance needs.

The Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill 2025 was the subject of a joint public hearing by the Senate and House Committees on Electoral Matters on 13 October 2025; the proceedings were characterised by stakeholder engagement from political parties, civil society, development partners, INEC and legal practitioners, reflecting the bill’s public law significance.

The Bill, as introduced, seeks to repeal the existing Electoral Act No. 13 of 2022 and to enact a consolidated Electoral Act, 2025; this is a legislative repeal and re‑enactment exercise intended to provide a comprehensive statutory framework rather than piecemeal amendments.

The stated policy objectives of the proposed statute are impartiality, enhanced transparency, strengthened administrative independence for INEC, accelerated litigation timelines, and measures designed to expand voter registration and participation — objectives which, if realised, would advance electoral integrity and democratic consolidation.

One of the cornerstone reforms is the prescription of a clear timetable for electoral events (Section 27(5–7)), mandating that presidential and gubernatorial elections be held not later than 185 days before the expiration of incumbents’ tenures.

STRENGTHS: This provision aims to ensure that electoral disputes and litigation are finalised well in advance of transfer‑of‑power deadlines, thereby reducing risks of constitutional limbo.

WEAKNESSES: Rigid calendaring may constrain remedial flexibility in the event of force majeure, legal challenges to the timetable itself, or delays in electoral logistics.

The Bill proposes that possession of the Permanent Voter Card (PVC) will no longer be compulsory for voting, on the basis that the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) does not depend on the PVC microchip and that registered voters may download and print a voter’s card when required

STRENGTHS: This could broaden access to voting by lowering a technical barrier for voters who lack physical PVCs.

WEAKNESSES: It raises questions of identity authentication, chain‑of‑custody, document forgery risks, and the adequacy of BVAS safeguards for offline or print‑based credentials.

Political parties would be required to submit certified lists of candidates not less than 210 days before election day, and only candidates who emerged from valid primaries would be accepted.

STRENGTHS: This long lead time is intended to enhance certainty, facilitate vetting, and reduce last‑minute substitutions.

WEAKNESSES: Such a requirement may curtail intra‑party democratic dynamism and create scheduling pressures for parties whose internal dispute resolution processes are incomplete.

The amendment narrows pre‑election litigation by limiting challenges to the jurisdiction where the dispute arose or to the Federal High Court in Abuja. Positive: jurisdictional clarity may expedite the disposal of disputes and prevent multiplicity of actions across jurisdictions.

WEAKNESSES: Limiting forum choice could impede access to justice for aggrieved parties far from Abuja and may raise constitutional questions on the right to fair hearing and a convenient forum.

The insertion of the National Identification Number (NIN) as part of the voter registration requirements (Section 10(2)(c)) seeks to harmonise biometric identification across public registers.

STRENGTHS: NIN integration promises improved data integrity, reduced multiple registrations and enhanced identity verification.

WEAKNESSES: Reliance on NIN risks disenfranchisement where NIN enrolment is incomplete, and it raises data protection and privacy concerns if statutory safeguards and due process are not rigorously defined.

READ ALSO: ADC demands suspension of Tinubu’s tax laws

The Bill recognises the voting rights of inmates (Sections 12(1)(d) and 12(2)), subject to INEC making arrangements for registration and participation.

STRENGTHS: This is an inclusivity measure that aligns with human rights norms and enfranchises a marginalised population.

WEAKNESSES: Practical difficulties in securing correctional facilities, ensuring secrecy of the ballot, and mitigating undue influence may complicate implementation and require detailed procedural regulations.

Provisions for mandatory early voting (Section 44) are introduced to facilitate participation by voters who, for stipulated reasons, cannot vote on the designated election day.

STRENGTHS: Early voting can increase turnout and accommodate voters with mobility or scheduling constraints.

WEAKNESSES: Without clear procedural safeguards, early voting could be susceptible to manipulation, chain‑of‑custody lapses, or opaque tabulation procedures that undermine confidence in final results.

The Bill makes electronic transmission of results compulsory (Section 60(5)), reflecting a statutory move to leverage technology for real‑time transparency.

STRENGTHS: Electronic transmission can fast‑track results collation, minimise human interference, and provide an auditable trail.

WEAKNESSES: Mandatory electronic transmission introduces cybersecurity vulnerabilities, dependence on network infrastructure, and potential single‑point failures; mitigating measures and contingency plans must be expressly provided.

To address perennial funding bottlenecks, Section 3(3) mandates the early release of funds to INEC to ensure timely election preparation.

STRENGTHS: Early appropriations could remove a principal operational impediment and enable adequate planning.

WEAKNESSES: Absent robust accountability mechanisms, early release of funds could increase risks of misappropriation or politicised funding interference, hence the need for strict fiscal oversight.

Complementing funding reforms, Section 5 obliges INEC to submit audited financial statements within six months after the financial year‑end.

STRENGTHS: This enhances financial transparency and facilitates parliamentary and public scrutiny, reinforcing fiscal probity.

WEAKNESSES: Audit timelines must be realistic given INEC’s operational capacity; failure to meet statutory deadlines without sanction may dilute the effectiveness of the provision.

The legislature is pursuing a concomitant constitutional amendment to transfer the statutory power to set election timelines from entrenched provisions of the 1999 Constitution to the Electoral Act, thereby granting the National Assembly and INEC greater flexibility.

STRENGTHS: Placing timetable authority within ordinary legislation allows responsive adjustments to administrative realities.

WEAKNESSES: Reducing constitutional entrenchment may raise separation‑of‑powers issues and could enable opportunistic manipulation of election timetables unless subject to stringent procedural safeguards and possibly supermajority requirements.

The Bill contemplates the re‑inclusion of statutory delegates’ voting rights in party primaries, a measure ultimately downplayed owing to cost and logistical considerations; instead, lawmakers preferred limiting participation to elected delegates while increasing the delegate quota from 30 to 50 per local government.

STRENGTHS: Expanding elected delegates is a compromise that preserves intra‑party representativeness without the logistical burden of reinstating statutory delegates

WEAKNESSES: This approach may still privilege party elites, complicate grassroots representation, and could produce intra‑party disputes over delegate selection and the expansion’s operational fairness.

If enacted, the amendments would likely yield an earlier election calendar, with presidential and gubernatorial elections slated for November 2026, approximately six months before the expiration of incumbents’ tenures.

STRENGTHS: The scheduling seeks to ensure that electoral disputes are resolved prior to the statutorily fixed handover on 29 May 2027, reducing the risk of transitional uncertainty.

WEAKNESSES: Accelerating the electoral timeline places increased logistical demands on INEC and political parties and may reduce the time available for thorough candidate vetting and civic education.

The Bill expressly targets weaknesses in the enforcement of electoral offences and seeks to bolster statutory penalties and investigatory powers.

STRENGTHS: Firmer sanctions and clearer offence definitions can deter electoral malfeasance and strengthen the rule of law.

WEAKNESSES: Effectiveness will depend on the capacity and political independence of enforcement institutions; without institutional reforms and procedural guarantees, increased penalties may not translate to improved compliance.

Campaign finance and political party operation reforms embedded in the Bill aim at transparency, including reporting obligations and limits on funding sources.

STRENGTHS: Calibrated campaign finance regulation can reduce the corrosive influence of illicit money and increase public confidence

WEAKNESSES: Onerous compliance costs and monitoring challenges may disadvantage smaller parties and independent candidates unless provisions include proportionality and capacity‑building measures.

Several provisions are expressly intended to enhance the operational independence of INEC, including statutory protections and funding arrangements.

STRENGTHS: Institutional insulation from partisan interference is fundamental to impartial election administration.

WEAKNESSES: Statutory pronouncements alone are insufficient; effective independence requires cultural change, resource commitment, and enforceable checks that deter executive encroachment.

The Bill’s emphasis on accelerated litigation timelines and jurisdictional clarity seeks to ensure finality of electoral disputes within constitutionally compatible windows

STRENGTHS: Expedited judicial processes can reduce prolonged uncertainty and enable timely installation of officeholders.

WEAKNESSES: Compression of timelines may strain court resources, impair the thoroughness of adjudication, and could inadvertently truncate litigants’ ability to gather necessary evidence — thereby impacting the substantive fairness of outcomes.

Implementation risks are manifold: harmonising BVAS operations with non‑PVC credentials, integrating NIN databases, ensuring secure electronic transmission, conducting early voting and inmate voting, and scaling delegate adjustments will require detailed secondary legislation, administrative guidelines, voter education campaigns, and investment in technology and human capital.

STRENGTHS: The Bill anticipates comprehensive reform and, if resourced properly, could modernise Nigeria’s electoral architecture.

WEAKNESSES: Institutional capacity shortfalls, funding deficits, and inadequate stakeholder coordination could frustrate legislative intent and erode public trust.

In sum, the proposed Electoral Act 2025 contains a mixture of progressive reforms ,enhanced transparency, funding predictability, expanded enfranchisement, and timetable clarity juxtaposed with new legal and operational risks relating to identity integration, technological dependency, compressed timeframes, and potential constraints on access to justice.

The ultimate efficacy of the amendments will turn on meticulous drafting, implementation fidelity, proportional safeguards, and sustained multi‑stakeholder oversight.

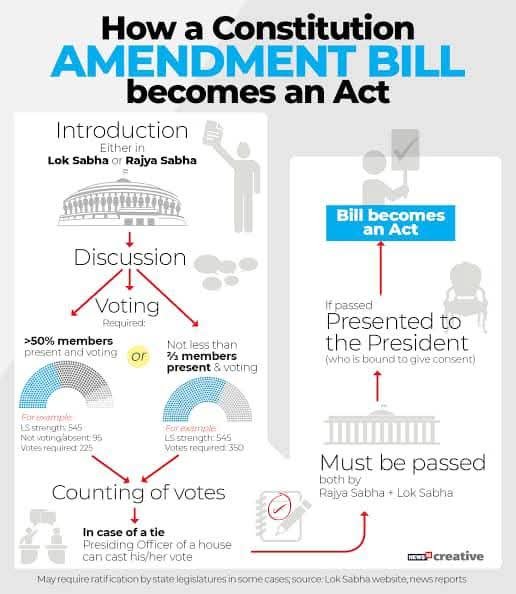

The legislative process continues: once both chambers of the National Assembly pass the Bill, it will be presented to the President for assent, at which point INEC will be required to revise its timetables and operational plans.

From a legal drafting and governance perspective, I recommend that the final instrument include transitional provisions, clear definitions, enumerated procedural safeguards, data protection clauses, contingency protocols for technological failures, and enforceable oversight mechanisms to mitigate the identified negatives while realising the positives intended by the reform.

This overview was written by Emmanuel Nicholas, who holds a first degree in law (LLB) and a Master of Laws (LLM), having concentrated his postgraduate studies in legal drafting.